A Brief History

| From the start, The Southern Courier recruited and maintained a bi-racial staff committed to reporting and disseminating the news in a professional and objective manner. It was never to be merely a journal of opinion. Reporters and editors were expected to become part of their communities, black and white alike, and not to engage in "drive-by" journalism or attempts at social change; to use their skills as journalists and not become community organizers or advocates for a single point of view; and to produce a quality newspaper that reached out beyond those who already agreed with the pro-civil rights perspective of its editorial page.

Michael S. Lottman, is the former editor of The Southern Courier (l965, l967-68). He currently practices law in Kingston, TN., a Nashville suburb, and is Chair of the Quality Review Panel, for Tennessee mental health. |

|

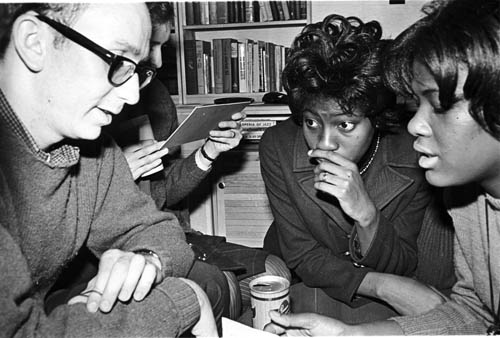

| Editor Mike Lottman covering a story and conferring with Courier reporters in the 1960's. |

|

In the spring of 1965, the Selma-to-Montgomery march and associated violent events were playing out in Alabama and in the national media. Meanwhile, staff members of The Harvard Crimson, the student-run daily newspaper, were coming up with the idea of publishing a paper based somewhere in the South that would communicate the daily reality of race relations and life in the black and white communities.

Soon the circle of young white Northerners working on the project expanded beyond the founders (Ellen Lake, now a lawyer in Oakland, California, and Peter Cummings, now a doctor and professor at the University of Washington) to other current and former Crimson editors and others who heard about the idea. One participant later remembered that he was lolling about at a Caribbean resort while the march for voting rights was going on, thinking he ought to be involved but not knowing what he could do. Soon thereafter the call came that changed his life forever.

The idea for a different kind of newspaper, soon to be christened The Southern Courier and based in Montgomery, Alabama, galvanized a large number of journalistically-inclined young people and gave them a way to contribute their special talents to one of the great social movements in American history.

The Southern Courier began publishing on a weekly basis with an issue dated July 16, 1965, and continued for some 176 more issues until late December of 1968. By the end, the influx of white Northerners had slowed to a trickle and much of the work of the paper was being done by local black writers, photographers, office staff, and distributors, and a few local whites as well. Dozens of Alabama's, Mississippi's, and the nation's best and brightest had come to work for the Courier--to tell the truth about race, to learn about journalism and about themselves-- and suddenly all of them were gone.

Although a few Courier veterans have kept in touch, most have not seen each other since the intense experiences of the middle and late 1960's--intense in terms of the events they covered and in terms of the never-ending scramble to gather, photograph, write, edit, print, and distribute a (usually) six-page weekly paper every week for 3 1/2 years. In the 38 years since publication ceased, the people who worked together on The Southern Courier had never held a reunion-- until 2006.

Some 40 veterans of the Courier experience turned up for the staff reunion held in Montgomery on April 1-3, 2006, with the co-sponsorship of Auburn University-Montgomery and in conjunction with the annual Clifford and Virginia Durr Memorial Lecture on Civil Rights. Mr. and Mrs. Durr were in effect the god-parents of the Courier and many of its young staff members; their home at 2 Felder Avenue in Montgomery was usually the first stop for new recruits until they got settled or were sent out to one of the paper's "bureaus" in Birmingham, Mobile, Tuscaloosa, Tuskegee, Jackson (Miss.), and other places where things were happening.

An historic marker was placed at the Durrs' home in April, 2005, to commemorate their commitment to justice and equality. Many of the "Courier kids" learned from Mr. and Mrs. Durr what those words really meant and just how much they cost the people who fought for them.

During the reunion, the Courier staffers reacquainted themselves with each other and with the Montgomery area, including sites they frequented (like the Durr home) that now are recognized as historic landmarks. The reunion featured an exhibition of the photographs of James H. Peppler, now a staff photographer for Newsday on Long Island (New York), whose work was invariably the most popular part of the weekly Courier. Another highlight was a luncheon address on April l by Taylor Branch, author of the definitive three-volume history of the life and times of the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., including the recently published At Canaan's Edge.

The activities of Dr. King and his Southern Christian Leadership Conference were frequent subjects of the Courier's coverage, and both he and the late Rosa Parks contributed articles to the paper on the tenth anniversary of the Montgomery bus boycott. One of the last special issues of the paper, dated April 13-14, 1968, reported on the assassination of Dr. King and its aftermath in Memphis and Atlanta (followed two months later by the death of Robert F. Kennedy in Los Angeles, for which the paper secured an eye-witness account on deadline from civil rights leader Charles Evers of Mississippi).

From the start, The Southern Courier recruited and maintained a bi-racial staff committed to reporting and disseminating the news in a professional and objective manner. The Courier was never to be merely a journal of opinion. Reporters and editors were expected to become part of their communities, black and white alike, and not to engage in "drive-by" journalism or attempts at social change; to use their skills as journalists and not become community organizers or advocates for a single point of view; and to produce a quality newspaper that reached out beyond those who already agreed with the pro-civil rights perspective of its editorial page.

At the most basic level, reporters were instructed to interview not only victims and protesters but also the store-keepers, police chiefs, or government officials who were the targets of accusations or complaints. County sheriffs, officials of local anti-poverty programs (the source of many disputes in those days), and other white power-brokers were not always eager to explain themselves, but most of them eventually responded, sometimes leading to a clearer understanding or the basis for a compromise solution. There was no way to prove it, but occasionally it seemed that the conspicuous presence of a Courier reporter at, say, the trial of a white person accused of assaulting an African-American resulted in a more vigorous prosecution and perhaps a different outcome.

|

| Vol. 4, No. 15 (April 13-14, 1968) covered the assassination of Dr. King. Click image to download the issue. |

The news was gathered (and photographed) as it occurred, written up and edited on Mondays and Tuesdays, and then put together--including type-setting and what would now be considered a primitive composition process--during an all-night session every Wednesday for delivery to the printers early Thursday morning. One time the waxed bits and strips of copy and headlines came loose in the morning sun on the way to the printers, leading to a demonstration of just how fast the paper could be pasted up when it had to be.

Usually about 30,000 copies of the Courier were run off and shipped mostly by Greyhound and Trailways buses to a network of distributors all over Alabama and eastern Mississippi, who sold the paper for ten cents a copy and kept half of that for themselves. Many a time one of the editors was awakened at an unseemly hour on Friday morning by one or more distributors who had not received their papers, which usually meant someone had forgotten to take them to the bus stations. Which usually meant the editor, cursing heavily, had to get out of bed and go do it by himself. These were usually good times for flat tires and the like to be discovered.

The Courier had major distributors in Montgomery and Birmingham, a few loyal newsstands that stocked the paper (usually the news racks on the corner would sell it but the fancy bookstores would not), and a mail subscription list of supporters, parents, and civil rights aficionados in the North.

Courier staff were paid from $20 to $75 a week, and it cost several hundred dollars to print each issue, bills which were often well in arrears thanks to an indulgent printer named W. Paul Woolley. Reporters and photographers also had to be equipped with (well-used) automobiles, and some of the younger staff had to be taught how to drive.

The Courier met its expenditures through single-issue sales, a few irregularly-paid advertising accounts (James M. Fallows, now a noted author and national correspondent for The Atlantic Monthly, came to the Courier to work on ad sales until he was allowed to try his hand at writing a few articles), and mostly through contributions from one major source (the Ford Foundation) and a host of smaller foundations and individual donors. One of the reasons the Courier faded out at the end of 1968 was that the issues around the war in Vietnam (and the loss of Dr. King's leadership) had diverted the attention of contributors and others from the cause of civil rights. Even so, the Courier did not close up shop until all bills had been paid, even the printer's.

It is sometimes said that The Southern Courier was in the vanguard of what is now known as the underground or alternative press. The Courier did in fact seek to provide balanced coverage of civil rights and racial issues that were frequently ignored by local papers and other white-owned media (and picked up by the national news only when they became telegenic or sensational). Eventually the Courier moved beyond its civil rights orientation to provide other news of the black community that was not reported elsewhere, such as high school and college sports and other human interest items. For quite a while, the paper ran a weekly gossip and society column that was first called "Party Line" and then, after a vigorous competition, was re-named "Rubber Neck Sue--Talking Folks' Business and Hers Too."

So The Southern Courier was an alternative publication in the sense that it began and evolved to meet needs that were not otherwise being met. If there is a difference between the Courier and today's alternative newspapers, it may be that the Courier was not filled with essays and opinion pieces but rather with painstakingly gathered facts presented in an objective manner. Facts, not arguments, were relied upon to enlighten and persuade (except of course on the editorial page, where few prisoners were taken).

Beyond trying to communicate the truth about racial matters, the Courier also saw itself as a training ground for young black men and women who might aspire to careers in journalism. So it was that Barbara Howard (Flowers) began setting cold type for the paper while she was still in high school and wound up three years later as the associate editor. So also another high-schooler, Viola Bradford, started out composing headlines for the Courier but soon became the paper's shining star, a brilliant reporter who could write a story about almost anything in such a way that almost anyone could understand. The Courier always tried to keep in mind the wide educational range of its audience, but with Ms. Bradford the gift of clarity came naturally.

Another young black woman, Sandra Colvin, became so knowledgeable about the complex black-white politics of "bloody" Lowndes County, Alabama, that the local FBI office frequently asked Courier editors what she was up to. Similarly, Mertis Rubin, writing from tiny Mendenhall, Mississippi, showed as much political insight and knowledge in her dispatches as any of the recognized (and much older) pundits. And Henry Clay Moorer, who did some reporting for the Courier from Greenville, Alabama, continued to contribute vivid and eloquent columns to the paper after he was called to service in Vietnam.

While it is not known how many (if any) of the Courier's minority staff actually ended up with long-term journalism careers, surely their visibility must at least have touched and inspired others. As one concrete example, Viola Bradford went away to school but came back to teach journalism for a time at Alabama State University.

But for all that the Courier did and tried to do, it may just have been that the example it set each day, of young people from varied backgrounds working together with great seriousness and common purpose, was the most valuable of all its contributions to a better and more just society. Such truly integrated business ventures were not as common then as they are now, and there were a few memorably frightening moments when staff members went out to eat together, gathered at someone's home in a "white" neighborhood, or went up to cover a session of the then all-white State legislature. But all these episodes ended safely, and the example of people going about their business, black and white together, not to prove a point but to get something done, was there for all to see for 3 1/2 years at a critical time in the transformation of Southern society.